I’m taking a note out of Mackenzie Thomas’s monthly retrospectives (x). Her writing reads like a dear friend’s voice memos, in a way that’s personal and effortless and also punchy. Like a conversation, as if she’d simply transcribed a casual chat – I’d told someone recently that perhaps that’s how you’d go about cultivating a personal voice in writing. Being that I rarely ever read my own writing out loud: journal entries or essays, emails, confessions, etc., I’d been toying with the idea that maybe by starting with verbal narration itself, you give voice to (both literally and metaphorically) your writing. Mulling over it for the past few weeks and in writing this, I think narration isn’t additive per se – as in to ‘give’, or to supplement some textual ‘original’. Narration, or more precisely, speech, is that origin.

Of course, human language began orally. Writing derives from speech, its systems and literacy came thousands of years after. Writing is speech’s more permanent manifestation. Where speech was solely impressed in the mind, it could henceforth be impressed on clay, written on papyrus, carved in stone, set in stone, reproduced, disseminated.

But there is a trade off for endurance and fidelity. Whatever expressiveness in speech is lost when we, like most people now, write primarily in silence. It’s such strange phenomena that so much of present writing begins at a keyboard, mute from conception save for the unfeeling clacking of keys. Even in handwriting – a rarity now, proof in simply looking around during your seminars – one only hears the scratchings of a pen. A far cry from its linguistic ancestors, where stories and legends were orally performed, and from infinitely diverse voices.

Apart from video essays (which I‘d argue is different for its reliance on visuals in conjunction with text), the rare slam poetry session, conference readings, a sermon: when was the last time you were read or narrated to? An audiobook? Reaching further back in time – by a teacher in school, or by a parent at bedtime?

It feels like writing nowadays is rarely given a chance to be narrated or vocalised, to be physically uttered, to declare or to shout, to whisper. That kind of writing is insensate (?) – it can be seen and read, obviously, and in some sense verbalised in the internal monologue of your mind, but it’s a sad feeling to think that most writing is never spoken in its own mother tongue of speech. Writing is, in some way, mute and deficient. It lacks speech’s rhythm, intonation, inhalations and exhalations, stress, volume, amongst others, those little things that make up emotion (prosody). But it is even more lacking if it is typewritten. Italicisation and bolding, underlining, capitalisation, etc. are all but poor, vestigial approximations of these aural nuances. In essence, writing lacks feeling, in the way that a text message cedes to a phone call. A letter is trumped by a conversation.

Typewriting seems to me the most base kind of writing, impersonal as it is. Conjuring the image of some faceless bureaucrat, it finds you with the corporate emotionlessness and austere formality of an email. All its letters are uniform, produced en masse, betrays no feeling. Worse still, they march in lines across pages like militant robots. Our familiar culprits: Callibri, Arial, and Times New Roman.

Obviously there’s bitter irony in prattling on about type in said type, but such are the limitations of working within online publication formatting – perhaps we should all start sending emails in Papyrus, in Impact, or better yet, in handwriting. Let’s publish books in calligraphy!

At least handwriting – while liable to this same poverty of feeling – makes up for it in its bodily-ness, and speaks legibly of its scribe. Handwriting evokes the physicality and motion of its writer: the hand and its path across the surface of the paper, smudged ink from a trailing, smothering left hand (da Vinci is widely believed to have written backwards on his manuscripts because of this).

During my travels, I started collecting my friends’ handwriting, and notes from receipts, price tags, post-its, etc. A veritable chirographic dictionary, textures of personality, legible and illegible, from far and wide.

Other identifiers of individuality:

a caret (which today I learnt it is not, in fact, called a carrot)

the different ways people awkwardly etch out their ampersands

if they cross their number 4’s and 7’s

the train of thought (or its derailment) behind a mistake scribbled out

double or single storey a’s (more indicative of nationality)

Leafing through my own journals, what I found and inferred:

abbreviating the “-tion” suffix (lazy)

biting letters (also lazy)

writing the number 5 and 6 and 9 from the bottom up

the use of the transpose proofreading mark (picked it up while learning Chinese)

Handwriting is at the very least variable. The idiosyncrasies of handwriting reveal feeling, indicates its humanity. A hasty scribble signals impatience, whimsy in the way the loops of a g or y are written, secrecy in a barely readable scrawl, etc. Handwriting is full of charm. I could go on and on for hours. The cafe’s daily special on a chalkboard; annotations in a second-hand book; a “Back in five minutes” sign on a closed shopfront.

For handwriting, the process of its conception is evident. It is worldly, for it leaves imprints, dents and furrows in paper. There is even the metallic, viscous smell of ink. Typing on the other hand (ha), is otherworldly. Copy and paste: it materialises without a trace, appears and disappears just as easily. Typing is supernatural: an apparition? In the sense that it lacks corporeality. Wave your hand and it passes through unimpeded like vapour. It doesn’t feel like anything because it is textureless; spectral. Or maybe like a bump in the night without a discernable source. It makes noise, but without any inkling of its creator. An orphan? There is something quite tricky about trying to place it.

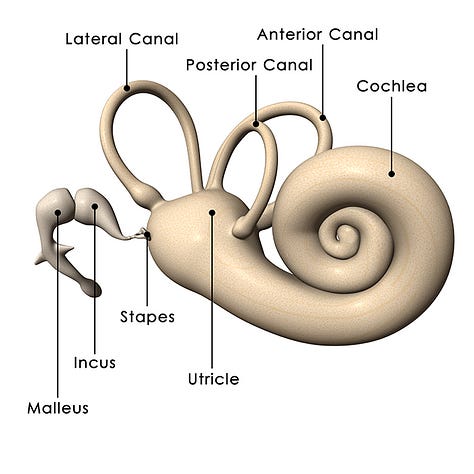

And what else? The intimacy of speech is also lost when it is translated into writing. The physical experience of sound feels incredibly intimate: to speak and to listen and to hear someone is bodily. Despite how immediate and effortlessly speech seems to occur, I get reminded about the array of organs and muscles and tunnels that have to work to produce our utterances. Sound waves pass from the vibrations of vocal chords, across space, reverberating into another's ears, becomes embodied. To want to be heard is perhaps not simply only a metaphorical imperative, but also a physical one. Having another’s tender words echo through and linger within your ear canals, rippling out through the rest of your body, seems to me immeasurably more romantic than whatever the written alphabet can offer. Hi-yeah, sing into my mouth.

None of this is novel or new thought, admittedly. And returning back to the question at hand, writing this I also realise it’s funny to expect some sort of authorial, personal ‘voice’ from writing. Clearly this ‘voice’ is a misnomer, purely metaphorical. There isn’t one we can literally or physically hear. Is it then simply diction or syntax we are concerned with, about flow, about perspective? Flipping it around, is the perennial obsession with finding a personal voice in what we read and in our own writing simply some sort of primitive, human instinct to physically hear and to be physically heard?

But also, the voice has an indescribable sweetness to it. So talk to, phone a friend, send a voice memo, speak to yourself, voice out your thoughts. Let your voice fill a room, fill a space. They still make amulets out of the roof tiles of Thai Buddhist temples, believing that the chants imbue them with spiritual energy — I like to think it’s not just the content of the prayers that do so, but also their verbal form that irreversibly transforms their surroundings.

The voice is a powerful instrument. It is versatile and boundless, even beyond intelligible words and speech: Bjork’s cacophonic Triumph of the Heart - Audition Mix, deconstructive dialogue of you’s and I’s in Still House Plants’ Headlight, the animal grunts that enter at 11:45 of Tubular Bells - Pt. II. Caroline Polachek’s unintelligible mutterings in Dang, sonic geographies in Hopedrunk Everasking — I imagine the ridges and crags and canyons its sound waves make.

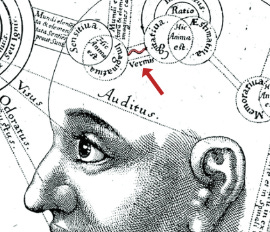

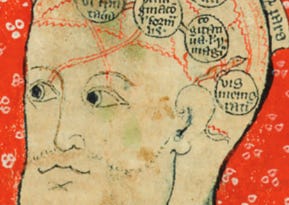

In my mind, the ear’s cochlea becomes a snail (or a nautilus; like the worm-like vermis in medieval neuroanatomical diagrams, see below), seeking out the cries of another, or simply just saying hello. So say hello back.

When reading, I hear my own voice in my head, but only when I make no concerted effort to empathise with the writer - I’m simply reading for myself and my own sake. Instead, sometimes I try to read with the writer’s voice playing in my mind (of course it’d require me having at least heard the writer’s physical voice before). The words may read the same, but the voice reads differently, and what and how those words make me feel could differ by hundreds of thousands of miles.

reminds me of your fyp topic